The State between Fragmentation and Globalization

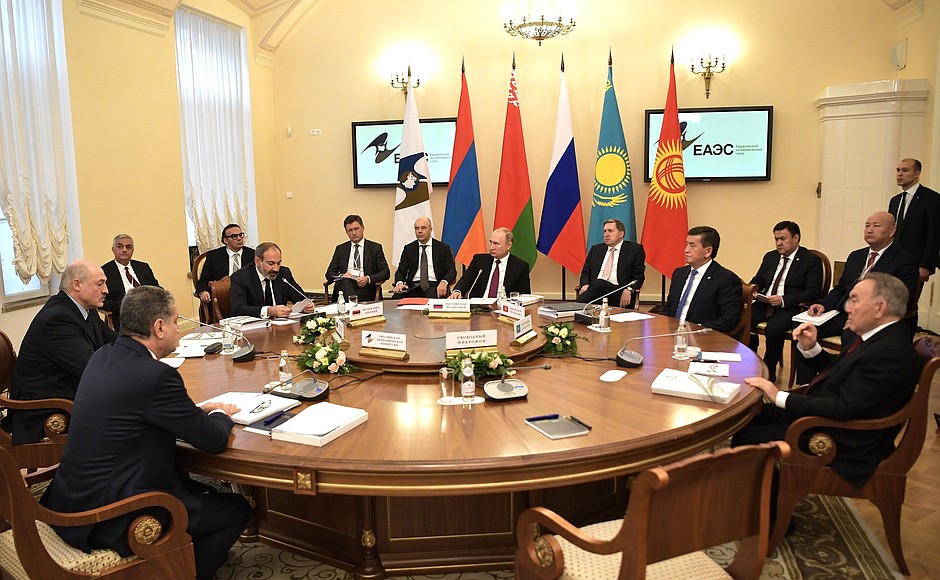

The terms used in the title of this essay were chosen to en able us to go beyond a purely legal approach in order to integrate legal facts into the broader legal context from which their meaning derives. State, fragmentation, globalization: these terms constitute the three poles of our analysis. The relations between them form the threads which tie it together, with the state, however, forming the central focus. It may well be supposed that the state is not terribly popular. Once again, it is being brought before the tribunal of history, this time a prospective or speculative history. At worst, the state is being asked to reabsorb or dissolve itself, even to allow itself to be divided up or reshaped by this pushing and pushing in two different directions. At best, the state must agree to transform itself. It is therefore useful to shed some light, at the outset, on this trial to which the state is being subjected (Section 1). From this basis, we can then move on in Section II to consider the observed, or predicted, break-up of the state: Is it indeed a case of fragmentation or, on the contrary, the promotion of a new model of the state? Finally, Section III concludes our analysis by examining this curious term ‘globalization’: What is it really? Is it not simply a contemporary mask for the c1assic old game of domination? Should we speak of globalization or of hegemony of the New World? I. The State on Trial The trial against the state raises questions about its domestic dimension as well as its international role, implicating it both on a political and legal level. Accusations against the state are by no means a recent phenomenon, but the problems currently facing it are based on new realities. And these new realities seem to indicate that fragmentation and globalization are complementary, rather than mutually exclusive, processes. –a. It is therefore necessary to focus on the dual nature of the state: on the one hand, it is a legal concept embodied in a set of organized norms, i.e. a normative system; on the other hand, it is a political body, structured on the basis of a principle of legitimacy which distinguishes it from any other body and gives it its unique identity. The state has a dual nature, but also a dual role: it is at once the expression and the totality of a domestic society and, at the same time, it is the foremost of international institutions. As the first amongst international institutions, the state is the pillar of classic international law. International law cannot be contemplated without the state, even less so can it be thought of as being against the state. The existence of international 01’ganizations does not create an exception to this, for the y are, as is well known, also inter-state, even intergovernmental, bodies for the most part. It is as an international institution that the state ensures civil peace and public order within its own territory, contributing to the peace and stability of the international society and carrying out its communication and cooperation functions with other states. It is in this dual role, domestic and international, that the state is today being brought into question. Firstly, concerning its internal homogeneity, national identity itself is being put to the test by regional-level demands, minority rights issues, cross-border relations, immigration, disrupted societies, and growing opposition between the rich and the poor. Secondly, territoriality, the traditional domain of the state, can no longer ensure the state’s enclosure nor can it protect this identity. Borders have become increasingly permeable to human, material, goods and service, and intellectual exchanges. In place of logic of a fixed juxtaposition, there is a tendency toward international nomadism, which not only effaces space, but also penetrates borders. Given this, the classic domestic/international distinction is being eroded. By the very nature of things, transnational questions multiply in number, whether they concern trade, the environment, or human rights. Finally, in imagining the state as a functional regulatory authority, a provider of norms and services, it can be seen that the state framework is ill-suited to such tasks. The opening up of markets and the globalization of trade is turning the state into an out-dated intermediate authority, dismissed by history. Too big for the local level, too small for the international, off the track, a framework for oppression, the state is ill-adapted, it disturbs, it annoys, it bothers, it gets in the way. It must be reduced in size before we can get rid of it. Moreover, has not the history of recent years been one of a drawn-out illness of the state, a decline which could lead to its ultimate crisis? – b. In all truth, despite its new accents, this trial has been under way for a long time. We can distinguish several phases or forms of dispute. Criticism of the state has always existed, not as the private domain of any one ideology in particular, but in the intersection of many: anarchism, legal idealism, federalism and Marxism, among others, have all criticized the state. Confronted with such criticism, the state has nevertheless shown immense historic vitality in being able to adapt itself to the most diverse political, economic and social realities without losing its fundamental traits, especially its international strategy. The state lives on in oblivion, and, thanks to its having been forgotten, in its transformations. Until now, it has managed to either bury its grave-diggers or rally together its enemies: the former Socialist countries, for instance, came from an anti-state ideology before becoming ardent defenders of state sovereignty. The current trial is, however, of a different nature, for it has been undertaken in the name of realism. The state is not being shunned in the name of an ideal society or a better future, but rather on the basis of a reading of the facts. Its framework is falling apart in many places: the collapse of the Soviet Union, bloody division in Yugoslavia, soft partition of Czechoslovakia, a perceived general artificiality of borders in Africa. The model of political structure offered by the state from its European origins appears to be coming under fire within its own cradle: Is the European Union not preparing to overtake it? The EU could indeed serve as an example for large-scale regional economic and political regroupings, thereby spreading a new model. –c. The two phenomena of fragmentation and globalization are thus not at all contradictory. In fact, they are all the less so because they create an option between two possible developments. These phenomena result from dynamics which are more complementary than contrasting, dynamics which mutually feed one another. We can certainly imagine two modes of evolution, or two ways out of crisis: the first from above, in a harmonious vision of a progressive realization of international federalism. The state would be no more than an authority amongst others in this gradation, without any particular legitimacy or status, a simple provider of services whose privileges have been abolished. The normative hope of Kelsen or the hope for solidarity of Georges Scelle can be recognized here. We may equally fear, however, a more tormented and tragic exit from below, taking the form of convulsive decomposition, planetary tribalism, a return to the state of nature and the law of the fittest. Certain recent examples of regression provide a worrisome preview of this scenario. We will not hasten a guess about which of these two directions will be taken, as the elements which would permit us to choose remain too unc1ear and, what is more, history never deals out more than a reshuffled ambiguity. To cite Jean Cocteau: «Trop de transformations s’ébauchent qui ne possèdent pas encore leurs moyens d’expression [[Too many transformations are set in motion which do not yet have a means of expression]].» It is not so much the concepts which are lacking, for the arsenal is full of them, but rather secure anchoring points which would allow us to ground them. Where we should find architects, discerning the mass, volumes and frames of future constructions from their half-built foundations, we strongly risk finding only lighting technicians who, by modifying the angle or intensity of the light or by moving the spotlights, will create only an artificial and fleeting reality. On the other hand, we can much more confidently analyse current data in their twofold dimension of fragmentation on one side, greater homogeneity on the other though not a spontaneous, undifferentiated homogeneity, quite the contrary, a homogenization pursued on the basis of a deliberate plan, an enterprise of multifarious domination. II. From Fragmentation to the Promotion of a New State Model –a. This fragmentation can be understood both quantitatively and qualitatively. On the quantitative level, firstly, increases in the number of states as a result of dissociation from former states is not a new phenomenon. However, two very different phases can be distinguished: decolonization and the collapse of the Socialist camp. With decolonization, largely encouraged by the United Nations, the international society became a machine for the manufacture of states. The number of states tripled in the space of some thirty years, and the state emerged more triumphant than ever. The new states strongly affirmed their sovereignty, their commitment to the principle of non-interference, the right to freely choose their domestic political, economic and social system. Confrontations between ideological systems turned the state into a sort of legal shell giving coyer to extremely diverse forms of domestic legitimacy. Of course, the state’s fundamental unit y, the hierarchical principle which renders the state a structure of internal domination, was maintained. As Montesquieu wrote, « … dans toute sorte de gouvernement on est capable d’obéir [[…in any type of government, one is capable of obeying]]». One could even add that one « must » obey. It is only at one level, that of apartheid, of racial discrimination, a prolonging of colonialism, that international action penetrates to the internal organization and politics of states. With the spread of the state phenomenon, the post-colonial era is therefore in large measure the era of the triumph of the sovereign state. It is protected by international rules which guarantee the exclusiveness of its domestic competences, its territorial integrity, and its political independence. One and the same movement promotes both the state and international law, and the development of this latter must be based not only on the free consent of each state but also on the consensus of the “international community of states as a whole”. In recent years, the growth in the number of states formed through dissociation from already existing states has developed a new dynamic, in a new context and spirit. It could be said that international society has become a machine for destroying rather than producing states. Break-ups and regroupings have developed or have the potential to develop precisely against this existing international society, despite the discrete resistance of its members and courts: this is true in the cases of the USSR, Yugoslavia, the dangers currently threatening certain African countries; it is equally true in the case of the reunification of Gerrnany, the dynamic behind which was more national than international. On a qualitative level, however, the resemblance between the two phases or steps of decomposition is stronger, but more in their rather negative elements. Indeed, in both situations – decolonization and post-Communism – we see that international society has not, until now, been in a position to ensure the development of new states or regimes, certainly not in terms of economic development, but also in institutional, legal, political and social terms. While international society has produced states, it has hardly known how to build them, neither the states it has manufactured nor those which have somehow formed themselves against it. In the case of decolonization, we are reminded of the failure of development law and of ail types of ‘new international order’ – economic, information, communication, and so forth. Even more serious is the fact that, after a few decades of independence, many of the new states formed in the 1950s or 1960s have been unable to ensure their political or social stability, thus remaining fragile and vulnerable. Has the “soft state” concept not been created in their name, implying a weakness, a feebleness? A concerted therapeutic effort has had to be undertaken to protect these states over the course of the past few years, with an extension of peace-maintenance operations in order to pre vent their destruction, if not also to allow their reconstruction: Africa, South-east Asia, and Central America provide various examples. The United Nations has had the tendency to become a hospital for the treatment of states, or even for perfecting a sort of compassionate protocol via humanitarian interventions. We can measure the extent of regression in terms of the goals set recently by development law. In the case of post-Communist states, which have only recently come into being, it is still too early to draw any clear conclusions. However, their difficulties can readily be seen. These difficulties are: political, with respect to the initial rumblings of transition to democracy, which cannot be reduced to merely monitored electoral operations; economic, with the transition towards a market economy, the recipe for which, like that for development, is still to be discovered; and social, with the problems of national identity and especially the minorities headache. We even get the feeling that the dissociation of constituent entities is now encouraged by certain international instruments, such as the recent Lisbon Declaration (3 December 1996), adopted within the framework of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), which integrates minority rights issues into security questions. Each minority, upon Joser analysis, tends to integrate several others into itself in such a way that this logic of Russian dolls can lead to indefinite fragmentation. It is no longer even just the idea of the nation-state which is being questioned, but the social framework of the state itself which risks crumbling into dust. A recent trend must be added to this picture, whereby each individual is viewed as a minority in and of himself, with the idea of plural allegiances, linked to multiple individual nationalities, to immigration phenomena, to individuals’ legitimate maintenance of citizenship ties with external entities, both of their origin and of their choice. This phenomenon of shared loyalties leads to a deep dissociation from the unique tie which identifies a state to its citizens. There is a strong risk of it leading to zero loyalty in practice. We should take care, therefore: what such a mechanism could set in motion, although no doubt unintentionally, is a planetary apartheid. Behind the mask of the right to be different, of a respect for cultural rights and cross-national ties, is a personal legal regime without borders, which could replace territorial law, that of the state. Who can fail to see that in this way we legitimize and legalize inequality, as each individual withdraws into his or her dispersed but homogeneous community? We would thus turn such a right into a machine for manufacturing, at best, ethnic states or, at worst, ghettos ridden with mafia and sects. Is this model, which Russia has failed to impose upon the Baltic countries, which Israel seeks to thrust upon Palestine, and for which Bosnia presents ail the scars, a desirable future for international society? At a time when the South African model has been rejected at domestic level and has caved in under general reproach, is it not tending to surreptitiously become a universal model in the name of the right of groups to an identity and to diversity? A rampant dissolution of states would be the result, but with no organized substitute. –b. Against this negative analysis, we can contrast the idyllic vision of a new state model, reconciling the state of law – a variation on the Rule of Law – and its particular identity with an international order founded upon common rules. However, outside the European Union – a utopia underway, but by this very fact geographically and culturally closed in – this is but a dream. The model for such an order is based on an abstraction rather than on descriptive elements. Nevertheless, this model is in some ways the positive vision or driving force for the ideal state, or a virtual state: it is still the state, but a state which is no longer engaged within and is subordinated without. It is not being contested that the state is still needed, not due to an institutional fetish but simply because nothing better has been found. A political model, even if imperfect, remains until it is replaced by another superior form. Even American hegemony, which we will come back to, comforts itself in maintaining states, at least under certain conditions. We can measure the necessity of the state by looking at the catastrophic consequences provoked, both at domestic and international level, by its collapse – recently in Yugoslavia, Somalia, Rwanda, perhaps soon in Zaire or in Albania. We see everywhere, and irremediably, a return to barbarism, with the civil wars which result from this collapse. The state or barbarism, such is the simple alternative with which international society is faced. On the legal front, we also see that international law has been caught off-guard by such situations. The collapse of the state falls outside the security mechanisms foreseen in the Charter of the United Nations. The international responsibility of the state itself, according to the terms of the proposed articles of the International Law Commission (Article 14), risks complete breakdown in the case of an insurrection on its own territory. In this type of situation, all international institutions – including other states – aspire to rebuild the state in question as quickly as possible, in their commitment to stability and international security. The internal withdrawal of the state, or the minimal state, occurs on an economic as much as on the legal-political level. Economic interventionism, the managed economy, the entrepreneurial state, the closed market state are all condemned, with the result that entire sectors supposedly managed by the state escape its control. Only recently were we talking about permanent sovereignty over natural resources. Now, attention focuses more on sovereignty over human resources, which is being called upon to make way for change. Job mobility, capital flight, and universal investment opportunism are factors in this dissolution. Not only does the European model of the welfare state appear to have become out-dated, but the very concept of public service has itself been brought into question. A general privatization mentality has tended to strip the state of ail that which does not fall within its strict executive functions, thus paralysing numerous sectors of its domestic normative capacity. In keeping with the new model, this somewhat reduced domestic normative capacity of the state should be channelled and controlled by judges rather than legislators. From this point of view, the pre-eminence of the legislator expresses a conquering and idiosyncratic conception of law: sovereignty of the state, mastery over itself, political voluntarism, law directed toward change, free organization of society from within, an instrument for rupture and action. The law is the sovereign power, the capacity for innovation and for decision-making; it is also the rule particular to a group. It is at the same time the act of political decision-making and the power of law as rule. The comeback of the judge represents, rather than a minimalist conception of law because legalization of social life can be extremely complex, a conception which is more reactive than active, more natural than wilful, more ethical than state-centred. This conception, moreover, is part of a more open and undefined framework than that of the classic state. We can slide easily from national to international courts, in a network of competences which pierce the screen of the state: in this way, the European Court of Justice and national courts are building a body of Community law which hems in the state; international penal tribunals can substitute for domestic penal competence; even the International Court of Justice, via its advisory opinions, can pass judgments on the security policies of states and can lay claim to controlling their defence powers (Advisory Opinion of 8 July 1996 on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons). This new model of the state, should it prosper, should be completed by the external subordination of the state. The state is asked to serve not so much as a filter between the internal and the external, but rather to facilitate passage back and forth, to act as an interface, not an enclosure. It is called upon to open its borders – to people, merchandise, information, cultural products. Already here, in this imposed opening up of the state to the four winds, we find one of the meanings of the term ‘globalization’. The state further learns from this term that it is called back to order: human rights have universal scope, as does respect for minorities, the right of families to be together, free movement of individuals, and humanitarian rights. The state exposes itself to reprimand, to coercive action in the most serious cases, if it fails to uphold these rights. Humanitarian intervention, ranging from NGO assistance to coercion by gunboats, whether legitimated by international instruments or not, can at any moment remind the state of this fact. The difference between international law and domestic law therefore tends to become blurred; state sovereignty is no longer just a word. Yet at the same time, international law has itself become blurred. We can thus read, in an example chosen at random from amongst many others, in the International Herald Tribune of 7 March 1997, the opinion of Thomas L. Friedmann on China and American policy in an article entitled ‘The Words Beijing Needs to Hear: Rule of Law’: Mao said, ‘We will never accept foreign capital.’ Then Deng came along and said, ‘We will accept foreign capital but never foreign norms.’ Now you say, ‘We will accept foreign capital and foreign norms, but not others.’ OK, we’ll wait for the next guy. These are very revealing phrases: no reference is made to international law, it is not even necessary to give it lip service. There is only a question of exporting and universalizing the values embodied in domestic legislation (‘foreign laws’) – the law of the United States, obviously. We could find no better way to argue that globalization – of markets, values, a model of the state, and of law which is its bearer – is the instrument of a policy, an intentional policy, a state-centred policy, of hegemony of the New World. III. Globalization: From a Global Society to the Hegemony of the New World We must first attempt to define ‘globalization’ before we can go on to observe that it is nowhere to be found outside the assertion of global American hegemony, which in itself is not without a number of ambiguities. –a. The term ‘globalization’ has enjoyed widespread usage in the media in recent years. We should, therefore, ask ourselves what the word actually means. It creates an image, but defining its precise content proves more difficult. What does this term add to the idea of a global international society, an idea that has been a reality since the time of decolonization? It undoubtedly adds the idea of increased economic, ideological and cultural homogeneity as well as the idea of solidarity, a qualitative acceleration of information flows, an interdependence of societies, a mobility of populations without borders. However, the expression seems above all to be a throwback to a dynamic and an objective, which can only be referred to as energy. It is devoid of content or particular values, which are, conversely, carried by terms such as ‘humanity’ or ‘international community’, so dear to development law and the globalistic aspirations of the 1970s. In this sense, globalization is the extension and accelerator of an ongoing process of transnationalization. It tends to increasingly exclude human, especially economic, activities from the jurisdiction of state, inter-state and institutional regulation. Thus, on the level of regulation of international relations, globalization would appear to be more of a problem than a solution: it is characterized, rather, by the erosion or abandonment of certain accepted methods of regulation. Yet even the most ardent zealots of this process admit that it cannot develop in a harmonious manner unless it is based on the mIes of the game, which can be inspired but not established by the partners to transnationalization themselves. Neither the anarchy competition of transnational companies nor the disorganized fervour of NGOs can suffice here. Reference currencies and regular financial circuits, for example, are needed. These rules of the game must, finally, stem from, or at least be foreseen by, state will, even the will of one single state, if it is dominant. More precisely, the new mIes of the game, or simply the erasing of the old rules, flow from the will of a state, that of the United States. In this sense, the real meaning of globalization must, therefore, be sought beneath the appearance of openness and homogenization. It is, in reality, a vehic1e of the media, a convenient term to indicate American hegemony. Globalization is the ideal of a New World with no shores. In a way, it is a new form of triumph of the state, but of a type of state which stands alone in its c1ass, and which has every intention of remaining this way. –b. Globalization is unattainable: in seeking efficiency, it challenges the institutional approach to international relations; in seeking homogeneity, it rejects or minimizes universality; in seeking domination, it sweeps aside multi-polarity. The institutional approach is the foremost domain of the United Nations. It is striking to observe that the globalization theme leads to a minimization of its role as well as the role of multilateralism developed within it. Not only do the General Assembly’s resolutions find themselves relegated to a lower rank, but the major UN conferences also appear to be things of the past. The multifaceted theme of the new economic, information or communications order has come to an end. The 1992 Rio Conference on ‘Environment and Development’ appears to be the last in the series. The New Information Order is CNN. With regard to the ambitions of a New Economic Order, the WTO is a minimal institution. More generally speaking, the collapse of Communism could have brought about the creation of a new principle of organization based on major texts. This has not been the case. Adjustments have rather been made by tinkering about and, at best, on the basis of the ‘pragmatic idealism’ boasted by the American administration. The Security Council itself has been sidelined from the resolution of conflicts – in the Middle East, in Central Africa – after, admittedly, some unfortunate experiences following the Gulf War. In short, the United Nations have, on the whole, been kept out of the new style of globalization; and with them, multilateral diplomacy, which is an inter-state, collegial diplomacy, has remained on the outside. There only remains one real moderator in international relations, and this moderator is a single state, the United States, not an international organization. As for universality, this would imply that a legitimate diversity of state policies should be recognized, argued for on the ground of compromise, without accepting the exclusion of certain states. This is pitted against a policy of near-universality, which is not only quantitatively, but also qualitatively,different. Universality allows identification of recalcitrant states, whichare few and isolated, labelling them ‘rogue states’, or deviant, uncontrollable, currently or potentially dangerous states. This identification is in practice done by the United States, which thus seeks to blacklist dissidents by exerting a twofold pressure on them: negativepressure through restrictive, even coercive, measures if they do not accept the rules of the game: Cuba, Iraq, Iran, Libya, Syria, for example, have been targeted in this way; positive pressure through the prospect of their advantageous integration into common regimes, as is the case, in particular, for China or North Korea, not to mention Russia. A number of quasi-universal regimes exist, which are generally thought of as common laws and which exert pressure on states remaining on the outside: the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, the World Trade Organization, and the recent Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, and the Chemical Weapons Convention. However, on numerous accounts, China, India and Africa stand completely or partially outside globalization – and most certainly outside these particular instances. Absent or recalcitrant states remain outside, however, for very different reasons, and are not able to constitute a common front either to reject or to support an alternative organizational strategy. A multi-polar approach for its part supposes that a recomposition of international society around large autonomous regional groupings would be accepted. Here, the European Union could serve as a preview and model. In this way, we could imagine continental or sub-regional poles, ASEAN for Asian countries, Japan, India, Africa (under more hypothetical conditions), in South America starting with Mercosur, in the area of the former US SR even with the Commonwealth of Independent States. However, such empirical reconstruction or decentralization, according to one’s point of view, has not been undertaken, and the prospects for autonomous organization of these groupings remain uncertain. Large regional groupings are certainly forming, but with the United States as the common denominator within them: NATO for Western Europe; OSCE for the area ‘from Vancouver to Vladivostock’; the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFT A) for the American continent, North and potentially also South; Asia Pacific Economic Co-operation (APEC); the peace process in the Middle East. As for Africa, it has little chance of regrouping if left to its own devices. It would be more a satellite type of lay-out, gravitation around a centre, rather than a balanced constellation which would be set up. This would parallel, even replace, true universalism. There is less need for the United Nations if, for instance, NATO, WTO, and the peace process work. –c. American hegemony without shores is the hegemony of a single state, based on varied methods and developing in multiple areas. It is virtually universal in extent and general in depth. This hegemony is state-centred in the sense that it does not require international channels for it to be exercised, and is even exercised against their dictates at times. In this way, the United States has affirmed its monetary dominance in rejecting, since 1971, international regulation which it itself instigated; in subsequently sweeping aside air transport regulation which was not initially contrary to its interests; in paralysing the United Nations while able to dominate the Organization. Not that the United States is in principal opposed to international organizations, it knows how to use the Security Council if necessary, to get rid of a Secretary-General who is not to its liking and to impose the one who is, to use NATO as it pleases, to promote the WTO as a mechanism for opening up markets, and so forth. However, the bases of American power – cultural, economic, monetary, military – remain essentially national. An example of this hegemonic view of the state is provided by the American approach to international law. It is largely perceived as the external projection of national law. It is in this way that the international actions of the CIA, actions said to be ‘covert’, that is to say, contrary to international law, have been supervised and authorized by Congress. We can be happy with American law from the perspective of the state, but how can we not see in it a process of deliberate, open and premeditated violation of international law? Domestic law is thus placed at the summit, even above the pyramid of international measures. The Rule of Law, as noted above, means the extra-territorial application of American law by any and all means. It is not necessary for hegemony to go any further. Allowing the continuation of an external world organized into states is a cheap solution, and distinguishes hegemony from imperialism. This latter, in fact, implies territorial domination, reminiscent of colonial empires, which is futile and costly. It is more efficient and economical to let states take care of their own domestic and international affairs, as long as, by subordination or imitation, they conform to the views of the United States. Beyond democratic rhetoric, the diversity of political regimes is not an obstacle or a problem. As in Chinese philosophy, the true distinction is not between political models, but between order and disorder, stability and chaos, the alternative which dominates international society. Hegemony is on the side of order and stability, not of territorial conquest or supranational integration. The methods of hegemony are opportunistic and therefore numerous. Unilateralism is practised on a large scale by the United States in several ways: by refusal, as in, for example, the refusal to sign the Convention of Montego Bay in 1982 or the veto of Boutros-Gali’s reappointment in 1996; by protection, in the superiority, as already mentioned, of American law over international law; and by promotion, in the desire to export American laws as the vehic1es of national interests, but also as a model from which others may happily draw inspiration: what is good for the United States is good for the rest of the world, even though the opposite is not true. Bilateralism is sought with selected partners, on certain questions – with Russia on nuc1ear issues or to establish a rapport with NATO, with China as a power external to the system, with Israel as the United States’ privileged ally. Regionalism allows the United States to be inc1uded, at the centre if possible, in all circles, as we have seen. However, regionalism external to US hegemony, i.e. regionalism which aspires to autonomy, like that of the European Union, is distrusted and can be fought if it appears to be a rival. Such distrust of, even hostility towards, the Euro or the Common Foreign and Security Policy could be the herald of a merciless battle against them. The allies are not partners, but advisers or subcontractors. Of course, they have a right to reprimand the hegemonic power, but in so doing, they would expose themselves to retributive justice which would make them give in. As for multilateralism, it takes the form of coercive multilateralism, as may be seen, for example, in the conditions of prorogation of the Nuc1ear Non Proliferation Treaty, the modification of the Convention of Montego Bay prior to its coming into force, and the adoption of the Nuc1ear Test Ban Treaty. These methods do not entail any preference for a particular type of legal instrument: General Assembly resolutions, formerly the domain of the non-aligned or of the challenged ‘automatic majority’, are now taken advantage of as, for example, with the adoption of the Nuc1ear Test Ban Treaty. The use of concerted non-conventional instruments is spreading within the framework of the OSCE, which is to say that soft law has not been brushed aside. As for Security Council resolutions, while the United States insists upon their authority, there is no hesitation in circumventing them when Security Council decisions are not to its liking – as was the case with the arms embargo concerning Bosnia. When it comes down to it, the dominant principle behind these methods is always opportunism at the service of cost effectiveness. –d. There are clearly a number of ambiguous aspects in the notion of American hegemony. These can be illustrated on several levels. Is hegemony, at its roots, a constraint or a choice for the United States? Does it correspond to some ‘grand design’ consistently pursued over past decades? Did it already exist in seed form at the time the nation came into being, with the conquest of national space and protection of the entire continent against foreign undertakings, followed by progressive investment in other continents? Could such an exceptionally rapid and ration all y orchestrated rise to power be explained in any other way? Has the United States not been endowed with a Messianic ideology from the very beginning? Has this ideology not placed the United States at the origin of all the successful grand schemes of the twentieth century? We could, however, maintain the contrary, that it is in spite of itself that the United States has been implicated in conflicts which it would have preferred to avoid such as the First and Second World Wars. This involvement forced the United States to assume historic responsibilities which it had neither sought nor wished. The challenge posed by Communism and the Soviet Union then threatened American principles and power, and the United States was compelled to react to this menace. It is true that the United States knew how to make the most of this situation in order to pursue its rise to global hegemony, which only Asia could now question. Ambiguity also lies in the justifications for, and objectives of, this policy. It can hardly be doubted that the United States currently wants to assume, to pursue and to accentuate its universal role, and globalization is its instrument. But does this desire correspond to a pursuit of narrowly conceived national interest, or to a more altruistic leadership in spirit, in the name of an overall vision of an international society? National interest is most often cited by American leaders, in the economic domain as well as in security matters. But this might be a means of gaining acceptance for an extensive foreign policy in a provincial Congress that is generally more concerned with domestic affairs. Apparent egotism would thus be masking a more noble goal, a break from the usual practices which hide small interests behind big principles. Does the enlargement of NATO, for example, represent a desire to ex tend freedom and stability in Europe, under the pressure of American voters of Central European origin, to permanently push Russia back eastward? Is American national security being called upon to dominate international security in the same way that American domestic law dominates international law? The same ambiguity characterizes the stability of hegemony. Once again, we find the central question of national interest, although in a different light. If hegemony is subordinated to national interest, this very fact makes it fragile. Hegemony in fact comprises only minimal engagement, repulses foreign rnilitary action, fears far-off losses, and demands that others finance its operations and deficits. It leaves situations for a long time, to rot or to develop into catastrophes, before intervening. It even awaits such catastrophes in order to best profit from intervention – as has been the case in former Yugoslavia, Rwanda and Zaire. It could also be recalled that during the two World Wars, the United States waited until Europe was devastated so as to be assured of benefiting from this self-destruction of European countries. This procrastination has until now been very successful. It is perhaps necessary in order to overcome a permanent temptation of isolationism. On the other hand, however, the desire to make its cultural model universal, to be on the cutting-edge of intellectual and scientific revolutions, to preserve ensured technological advancement, to master all areas of communication and to be a global centre can only contribute to the lasting stability of this hegemony. A final example of ambiguity can be found in the perceptions others hold of American hegemony. It is remarkable that, with only a few exceptions, this hegemony IS not only accepted, but indeed desired – a positive view which equally contributes to its stability, and is largely due to the United States’ skills in presenting itself. It knows how to wait, as it did during the two World Wars, and as it does today with respect to the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. All in all, the twentieth century has been spent waiting for the Americans. Under these conditions, their arrival, once it does come, is on the whole hoped-for and welcomed. Moreover, it is generally the positive aspects of their presence that receive attention: individual freedom, intellectual openness, technological advance, and capacity for innovation, among others. The United States first projects its culture and cultural products: in short, American hegemony is first and foremost the Disneyland image. With this benign, endearing appearance, American hegemony becomes desirable, in such a way that it would be unfair to belittle this hegemony by considering it a merely predatory quest for domination, for which history has offered many examples. Those who denounce it or fight it have often awaited it, solicited it, supported it, even profited from it. Beyond perceptions, as well as renunciations, we can also objectively observe that this power is cohesive and tends to gather more power around itself. The attraction to power and the phenomenon of aggregation, which it provokes, are virtually irresistible, and the great power has many best friends. It can choose from amongst numerous candidates with whom it has privileged relations. International society’s lack of a structural organizing power leads to a tendency to rally around the one state, or group of states, which embodies the developing hegemony. A time of weakness will come, however, and a time of bitterness, even of revolt. But for the time being, power and the perception thereof are on the side of the United States. We must not misjudge the European project, however, which, despite such a long and difficult gestation period, has after all made considerable progress. If Europe as a spatial entity should become, or return to being, Europe as a world power, which is a possibility and perhaps even its design, then globalization, will no longer have the unipolar or unilateral dimension it has today. Otherwise, if the current predominant themes continue, there is a strong risk that the United States will have to be substituted for Rome and Americans for Romans in the following observations by Montesquieu: Il fallait attendre que toutes les nations fussent accoutumées à obéir comme libres et comme alliées, avant de leur commander comme sujettes … Ainsi Rome n’était pas à proprement parler une monarchie ou une république, mais la tête du corps formé par tous les peuples du monde … ils ne faisaient un corps que par une obéissance commune, et, sans être compatriotes, ils étaient tous Romains. [[It was necessary to wait until all nations had become accustomed to obeying as free and allied, before commanding them as subjects … Thus Rome was not, properly speaking, a monarchy or a republic, but the head of a body formed by ail the peoples of the world … they created a body only through common obedience, and, without being compatriots, they were all Romans.]]